SkyTide

Official publication resource of Gramatik LTD

Related Posts

The Strange Power of Stuff: How Commodities Play Mind Tricks on Us

Take a moment to think about your smartphone. At first glance, it’s simply a collection of metal, glass, and circuits assembled for your convenience. But step back, and you realize something strange: your phone, along with other items we buy and sell, seems to carry a value beyond its mere function. It’s almost like it has its own social life, influencing your interactions and even how you relate to others. This mysterious transformation is what Marx called the “fetishism of commodities”—and it reveals much about our modern economy.

The Magic Trick of Value: How Products Become Social Players

In everyday life, a chair or a shirt is valued based on how useful it is. If you need to sit, the chair has purpose; if you’re cold, a sweater is valuable. This part of a commodity—its use-value—is easy to understand. But commodities have a second, hidden layer that’s harder to grasp: exchange value. This is the invisible, monetary worth assigned to an item, which only emerges when we compare it with other things.

Imagine you’re shopping online. A set of headphones might be listed for $50, a pair of shoes for $100. Though they serve entirely different purposes, they can be compared in terms of price. Suddenly, these items take on a social dimension: they’re not just functional, they have worth in relation to other commodities. This social life of commodities can even seem as if it’s independent of human labor—the labor that made them valuable in the first place. And that’s where the “fetishism” comes in.

Value’s Illusion: Why We Forget Who Creates Wealth

Marx pointed out that as commodities become valuable, they mask the labor behind them. Your phone, for example, carries a price tag based on its market worth, not on the grueling hours worked by factory laborers or the time invested by software developers. This market value creates a sense of separation; it seems like commodities have a value of their own, detached from the people who made them.

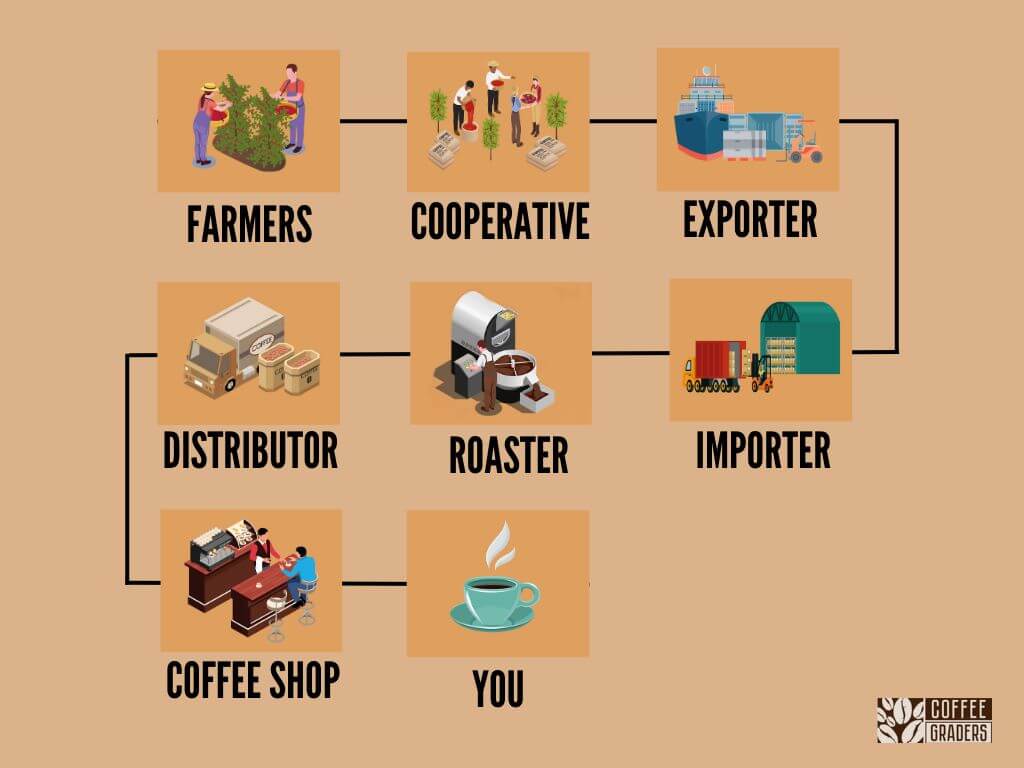

Think of a $3 cup of coffee. You might not think of the farmers, baristas, or logistics workers behind it. The exchange value creates a veil, a kind of social “mask” that hides the human work poured into that cup. This mask turns commodities into mysterious objects that appear to have worth all on their own, making us focus more on the price than the human effort they embody.

How Commodities Shape Our Reality: A Shared Delusion?

In a market-based society, value is something we all agree upon unconsciously. When you buy a coffee or a car, you’re participating in a network of social relationships, although you may not feel it. Each exchange creates a “relationship” between products—coffee to dollars, dollars to smartphones—and in turn, these exchanges dictate how society values different kinds of work. This creates an odd hierarchy where items are rated not by usefulness but by their price in comparison to each other.

For example, if a diamond is worth more than a ton of iron, we start valuing the diamond more, even though iron is essential for building and infrastructure. This price-focused mindset makes us forget that value is a shared social understanding, a consensus that society creates and maintains.

The Real-World Magic of Money: Why Everything is a Commodity

The weirdest part of commodity fetishism is money itself. Imagine a situation where everything you own could be represented by a single, universal item—a dollar bill. Money simplifies transactions by acting as a universal measure of value. Your phone, lunch, or sneakers can all be represented by the same dollar amount, making them exchangeable and comparable in the marketplace. Money becomes the ultimate fetishized object, concealing the true social relationships behind it and giving items a life of their own.

In this way, money doesn’t just make trade easier; it actually creates the social structure of the marketplace. When we talk about a $1,000 phone, we’re not just speaking about a device. We’re referencing its “rank” in a world of commodities, an imaginary hierarchy that we all accept.

Beyond the Illusion: Seeing the Real Value

The fetishism of commodities teaches us to see beyond the surface of everyday transactions. If we look deeper, every product we buy connects us back to human labor, human needs, and a network of social interactions. Whether you’re holding a phone or sipping coffee, you’re part of a complex system where the invisible labor of others makes those items valuable to you.

By pulling back the curtain on commodity fetishism, we see our economic lives for what they are—a shared reality created by human work and social agreement, even if it appears as an illusion of price and worth. The true value isn’t in the product itself but in the human lives it touches and connects along the way.

Stay tuned as we keep unraveling the fascinating web of value, revealing the deeper truths hidden in our everyday economics!

Open a trading account with a Broker right now

Read the Risk Warning before you register

Find more interesting stories and news about investments on our subreddit XGramatikInsights.

FXgram

The Ugly Truth About Trading

Related Posts

Risk Warning: Trading Forex and Leveraged Financial Instruments involves significant risk and can result in the loss of your invested capital. You should not invest more than you can afford to lose and should ensure that you fully understand the risks involved. Trading leveraged products may not be suitable for all investors. Before trading, please take into consideration your level of experience, investment objectives, and seek independent financial advice if necessary. It is the responsibility of the Client to ascertain whether he/she is permitted to use the services of the website based on the legal requirements in his/her country of residence.