SkyTide

Official publication resource of Gramatik LTD

Related Posts

The Two Sides of a Commodity: What Gives Something Value?

In the world of capitalism, the wealth we see all around us boils down to one thing: an overwhelming mountain of stuff—commodities. These commodities are the basic building blocks of wealth. So, to understand how wealth is created in this system, we need to start by breaking down what exactly a commodity is.

At its core, a commodity is an object that exists outside of us and satisfies some kind of human need or desire. Whether that need is a practical one, like hunger, or more abstract, like wanting the latest smartphone to keep up with trends, it doesn’t matter. If something satisfies a need, it becomes useful. Think about it: iron can build skyscrapers, paper helps us write ideas, and diamonds make dazzling engagement rings. These things are all useful in different ways and in varying amounts.

Every commodity has two key sides: use-value and exchange-value. The first side, use-value, is straightforward. It’s the practical use of an item. Iron is useful because you can build with it. Corn is useful because you can eat it. A phone is useful because it connects you with others. This usefulness—its use-value—is tied directly to the physical properties of the item. You can’t separate the usefulness of corn from corn itself.

But use-value isn’t the full story. A commodity only becomes part of the capitalist system when it’s exchanged for something else. That’s where the second side, exchange-value, comes in. This is where things get a little more interesting.

What’s a Commodity Worth?

When we exchange things—like a quarter of wheat for some iron or gold—the relationship between these things isn’t random. There’s something deeper going on that connects them. The exchange-value shows how much one commodity is worth in relation to another, but it’s not just about their use. For example, a bar of chocolate and a gallon of gas don’t seem to have anything in common, yet they both have a price that allows them to be exchanged.

Imagine walking into a grocery store. On one shelf, you have bread. On another, you have a bag of chips. While both serve different purposes, we can still compare their values using money. A loaf of bread might be $3, and the chips could be $2. The numbers don’t care that bread feeds you and chips are more for snacking. What these numbers show is how much work went into making them.

The Labor Behind the Scenes

So, what makes two totally different things comparable? It’s not their physical properties, like their taste or shape—it’s the human labor that went into producing them. Whether you’re weaving fabric or writing code for a new app, all types of work can be boiled down to one essential ingredient: labor power. This labor power gets poured into commodities and becomes the hidden thread that ties everything together.

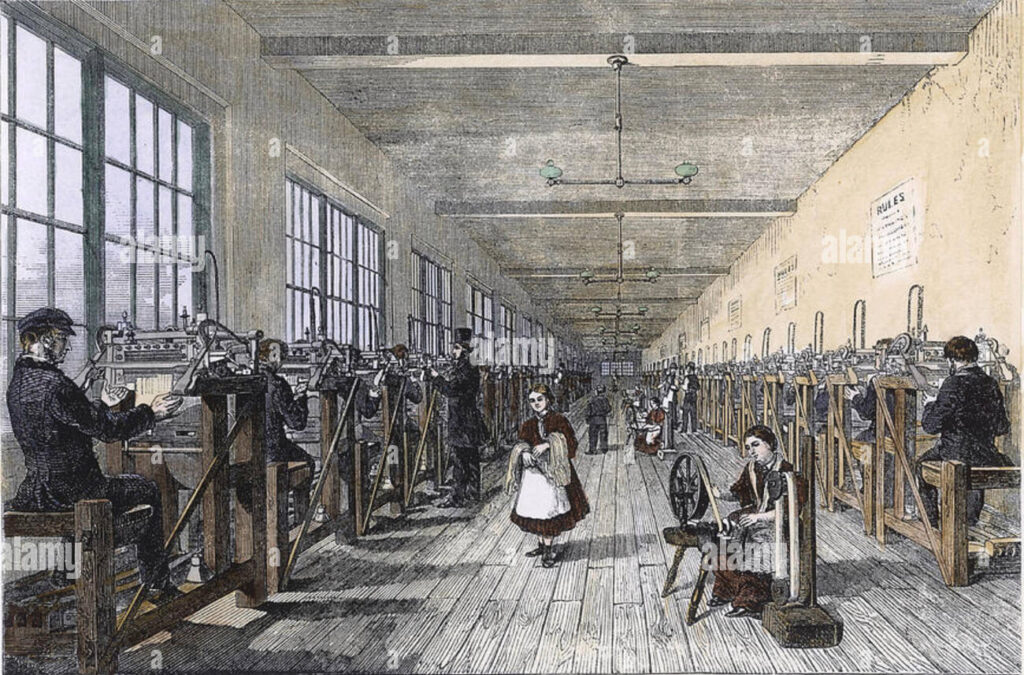

But not all labor is equal. It’s not just about how long someone works. It’s about how much labor is socially necessary. Picture this: in the early 1800s, hand-weavers in England took hours to make cloth. Then, power looms were introduced, cutting that time in half. Did the value of cloth stay the same? Absolutely not! The value dropped because now it took less labor to produce. The amount of labor needed to make something determines its value.

This idea is still true today. Think about the tech industry. Ten years ago, it might have taken a team of engineers months to develop a new app. Now, with better tools, frameworks, and cloud services, that same app can be built in weeks. The value of software development shifts with the productivity of the labor involved.

The Impact of Innovation

In Marx’s time, he used the example of diamonds and gold to show how difficult labor affects value. Diamonds are rare and hard to find, so they take a lot of effort and time to mine. Therefore, they are very valuable. But imagine if we could cheaply manufacture diamonds in a lab. Suddenly, their rarity would vanish, and so would their high value. The same labor that previously created scarcity would now be applied to make these commodities more common, lowering their value.

A modern example of this might be the rapid improvement in manufacturing electronics. The first flat-screen TVs cost a fortune. Now, you can buy one for a fraction of that price because the labor needed to make them has become more efficient. As the productivity of labor increases, the value of the commodities decreases.

The Big Picture: Value is Always About Labor

Here’s the kicker: value only exists because of human labor. If no work goes into something, it doesn’t have any value, no matter how useful it might be. Air is essential for life, but you don’t pay for it because no labor is required to produce it. On the other hand, a software developer’s time has value because they’ve expended labor to create something you can use, like an app or a service.

So, to summarize this first part: a commodity is both useful and valuable because human labor has been poured into it. But how much it’s worth depends on the amount of labor, and that value changes based on how efficient or productive that labor is.

This is just the start. In the next section, we’ll dive deeper into how labor, value, and commodities interact with each other in even more fascinating ways. Stay tuned!

Open a trading account with a Broker right now

Read the Risk Warning before you register

Find more interesting stories and news about investments on our subreddit XGramatikInsights.

FXgram

The Ugly Truth About Trading

Related Posts

Risk Warning: Trading Forex and Leveraged Financial Instruments involves significant risk and can result in the loss of your invested capital. You should not invest more than you can afford to lose and should ensure that you fully understand the risks involved. Trading leveraged products may not be suitable for all investors. Before trading, please take into consideration your level of experience, investment objectives, and seek independent financial advice if necessary. It is the responsibility of the Client to ascertain whether he/she is permitted to use the services of the website based on the legal requirements in his/her country of residence.